The Shrine of Sword & Sorcery!

Let me tell you of the days of high adventure!

Sword & Sorcery! Just the name conjures up images of larger-than-life heroes, scheming magicians, beasts from beyond and drawn blades thirsting for the red wine of battle. Brawny barbarians, wicked warlocks, thick-thewed thieves, able-bodied amazons, consummate cavaliers, and all the mad kings, imperiled maidens, sinister priests, and fat merchants they could hope to meet on their travels. Epic adventure in a bygone world, in more ways than one.

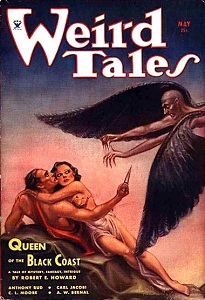

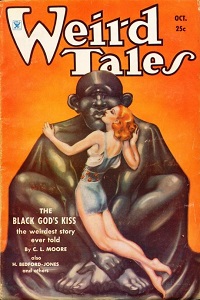

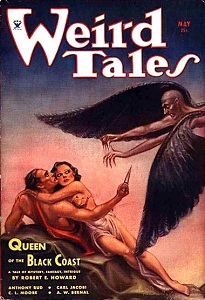

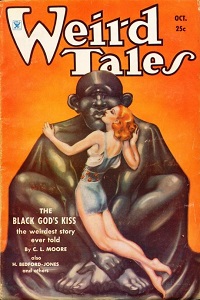

Sword & sorcery is a genre of fantasy fiction which emerged in the pages of Weird Tales in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Arising from a melange of influences and authorial correspondences, the genre as it is most commonly understood today was codified by Texan writer Robert E. Howard (1906-1936). Howard created a number of the genre's most notable, most enduring, and most revered characters, including Kull of Valusia, Bran Mak Morn, Solomon Kane, and of course, the iconic Conan of Cimmeria, known almost exclusively in popular culture as Conan the Barbarian. At the same time, other Weird Tales contributors were experimenting with their own styles. Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961) delved deeper into the genre's roots into cosmic horror in his stoies set on the prehistoric continents of Poseidonis and Hyperborea, the fantastical medieval French province of Averoigne, and the far-flung post-apocalypse of Zothique. In "Black God's Kiss" and its sequels, C.L. Moore (1911-1987) created the genre's first leading heroine in the iron-willed Jirel of Joiry. Clifford Ball (1908-1947) more directly aped Howard's style in his three tales, with enjoyable results. Nictzin Dyalhis (1873-1942) wrote of men inhabiting the bodies of their previous incarnations in fantastical lost pasts. Fritz Leiber (1910-1992) created the picaresque duo Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, a barbarian and a thief in a dangerous city. A late entry in this golden age, Gardner Fox (1911-1986) debuted Crom the Barbarian, the first sword & sorcery hero in comic books, in 1950.

While these tales were popular with Weird Tales' readership, it wasn't until the 1960s that the genre went mainstream with the so-called Lancer Conan Saga, a reprint series of Howard's Conan stories - re-arranged, edited, altered, and even augmented by L. Sprague de Camp (1907-2000) and Lin Carter (1930-1988). While controversial among literary purists, the series was hugely successful and opened the gates for authors and imitators looking to satisfy the public's sudden appetite for sword-slinging barbarians.

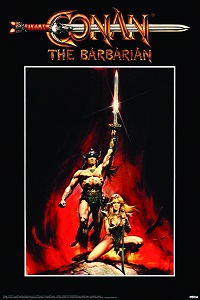

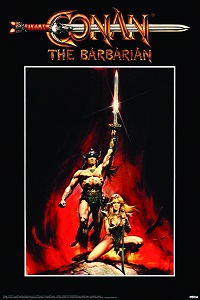

For the next few decades, barbarians ran amok in the literary scene, many of them deliberately cast from Conan's mold. John Jakes (1930-), seeking to write more of the kinds of stories he enjoyed from Howard, created the well-regarded Brak the Barbarian; Gardner Fox returned with the schlocky, tongue-in-cheek Kothar and Kyrik series. Charles R. Saunders (1946-2020), reacting against the poor representation of black people in the pulp tradition, created the Imaro and Dossouye, who adventured across fantastical versions of historical Africa. Poul Anderson (1926-2001) drew on his own Danish heritage in the novels The Broken Sword and The Merman's Children, which blended sword & sorcery with historical fiction and mythology. Karl Edward Wagner's (1945-1994) immortal, amoral Kane made his debut during this period. Reacting against the proliferation of meatheaded barbarians, Michael Moorcock (1939-) created Elric of Melniboné, a sickly, aristocratic albino sorcerer. Anthologies like The Mighty Barbarians, Amazons!, and Flashing Swords! proliferated. Conan the Barbarian opened in theatres in 1982, leading to a flood of copycat films that lacked its emotional core, philosophical undertones, and budget.

By the 1980s, buried beneath an ungainly heap of superficial Conan copycats, sword & sorcery was a joke, a genre without literary merit fit only to satisfy the power fantasies of immature teenage boys. With James Silke's (1931-) Death Dealer novels of the late 1980s, based on the paintings of Frank Frazetta, the genre breathed its last gasp of mainstream relevance and largely went underground.

What makes Sword & Sorcery different?

This is an interesting question, and not necessarily an easy one to answer! Genre boundaries are always fluid, especially within a larger super-genre like fantasy, and it can be hard to define exactly where a work should be categorized - and some works defy categorization altogether! Nevertheless, fans and scholars have come up with a few general criteria for what makes sword & sorcery distinct from other styles of fantasy, in terms of tone, structure, and world-building.

- Action-Packed Heroes: Most sword & sorcery protagonists are warriors, thieves, wanderers, sorcerers, or some combination of the three; what they are not, generally, are simple, innocent folk forced by necessity to leave to comfort of home to combat evil. Most are already out there, stricken with wanderlust and the love of battle to see the world and drink in its many pleasures in the short time they have. They are men and women of action, larger than life and usually larger than most of the people around them as well!

- Black Magic: The "sorcery" part of the name is not messing around! As opposed to something like Harry Potter or Dungeons & Dragons where magic is simply a tool and so commonplace as to be nearly mundane, magic in a sword & sorcery yarn is rare, dangerous, diabolical, and volatile, often obtained through dealings with dark gods and liable to corrupt or betray its wielder. Not all those who use it are evil - most heroes find themselves teaming up with spellcasters from time to time, and some even use it themselves - but it tends to have a sinister, otherworldly air often omitted in other fantasy subgenres.

- Personal Motivations: As a general rule, sword & sorcery heroes are not out to save the world. They might save a kingdom, on occasion, but usually more for personal reasons than any noble calling. Greed, vengeance, pragmatism, lust, and simple curiosity are all powerful motivators to the sword & sorcery hero. This isn't to say they lack any finer feeling, of course; it's as much about the scale of the story being told as the hero's morality.

- Horror Influence: Robert E. Howard, C.L. Moore, and Clark Ashton Smith were all hugely influenced by H.P. Lovecraft's weird pulp and cosmic horror tales, and the use of horror elements has remained prominent to this day; this often goes hand in hand with the points about magic above. Demons, extradimensional monster, extradimensional demonic monsters, dark gods, evil sorcerers, savage atavisms, human sacrifice, moreal degeneracy, and other horror staples are all common in sword & sorcery.

- Short Format: Because it originated in the pulps, most of the formative works or sword & sorcery were short stories or novellas. While novels have become more and more common over the years, anthologies and magazines have remained prominent vehicles for the genre.

- Outsider Perspective: Most sword & sorcery heroes are, in addition to men and women of action, outsiders in some way - not outcasts, necessarily, but outsiders. Guys like Conan, Kothar, and Brak are habitual wanderers whose adventures take them to strange places; Imaro, Dossouye and Fafhrd are banished from their homelands; Elak of Atlantis is a prince who rejects his responsibilities; Jirel of Joiry is an embattled noblewoman ruling in her own right; Duar and Kyrik are deposed kings haunted by weird magics; Rald and the Gray Mouser are thieves. Rare is the hero who stays in their hometown to become a pillar of the community.

- Elves Need Not Apply: Steretypical "fantasy races" like elves and dwarves are rare in sword & sorcery, and a fully integrated multi-species society of the kind often depicted in modern Dungeons & Dragons is practically unheard of. While non-human sapient beings are often present in stories, they tend to be rare and mysterious in-universe, small pockets of inhumanity dwelling in remote places and lost ruins. In keeping with the genre's origins in pulp and horror, they tend to be ape-like atavisms, reptilian remnants of past civilizations, or strange, eldritch beings from other worlds. They tend to be malevolent, though some are presented as worthy adversaries with their own sort of nobility, and a small few are benign or benevolent.

Sword & Sorcery on Film

The precursors of cinematic sword & sorcery lie in the historical epics and swashbucklers like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Italian pepla like Hercules (1958) and Colossus and the Amazon Queen (1960), and Harryhausen mythology-fantasy like The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963); however, the genre really took off with the 1981 release of Clash of the Titans and especially Conan the Barbarian the following year. The next fifteen years or so saw a flood of barbarian movies, often made with low budgets in Italy. Sword & sorcery has maintained a stronger presence in film than it has in literature over the last few decades, but most modern films in the genre are low budget, direct-to-video affairs. Here are some of the most notable sword & sorcery films:

- Conan the Barbarian (1982): The most famous and influential sword & sorcery film, loosely adapted from the genre's most famous and influential hero. Arnold Swarzenegger doesn't much resemble Conan as Howard described him, in appearance or personality, but Conan the Barbarian is so good in its own right that it hardly matters. A weighty, luxurious film, it balances its epic tone and philosophical musings on fate, family, and the nature of power with two-fisted action, physical comedy, and an incredible score from Basil Poledouris. Other notable names include James Earl Jones as the evil but charismatic sorcerer Thulsa Doom, Max von Sydow as the bereaved King Osric, and Mako as the wise and eccentric Wizard of the Mound. A sequel, Conan the Destroyer, followed in 1984. Lighter and sillier, Destroyer is in some ways closer to Howard's original stories, but lacks the weight and depth of its predecessor. Schwarzenegger and Mako return, joined by Grace Jones as the fearsome Zula, Wilt Chamberlain as the suspicious Bombaata, and Pat Roach as the evil Thoth-Amon.

- The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982): A deposed prince grows up to become a barbarian mercenary and returns to reclaim his kingdom. Mostly what I remember is he has a sword with three blades and he can shoot the extra blades out of the hilt at bad guys, which is rad.

- The Beastmaster (1982): Very loosely adapted from a 1959 Andre Norton novel, The Beastmaster stars Dar, a barbarian who can talk to animals. He main companions are a tiger, a hawk, and two ferrets. Was followed by two sequels; Beastmaster 2: Through the Portal of Time (1991) brought the action to then-modern Los Angeles, and Beastmaster III: The Eye of Braxus (1996) looks to go back to more traditional sword & sorcery fare. Was also adapted into a television series, Beastmaster (1999-2002).

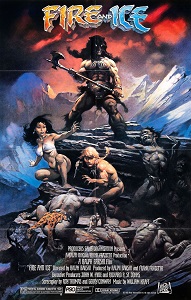

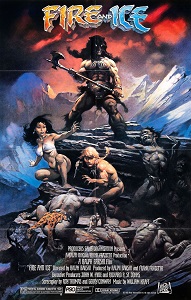

- Fire and Ice (1983): An animated epic, Fire and Ice is most notable for its character designs, created by iconic fantasy artist Frank Frazetta, and its use of rotoscoping.

- Deathstalker (1983): A grimy, brutish, amoral movie, in which the titular barbarian mercenary, Deathstalker, is a killer and attempted rapist barely better than the evil sorcerer he's trying to overthrow. It was followed by several sequels; 1987's Deathstalker II inexplicably, but mercifully, reimagines Deathstalker as a swashbuckling prince of thieves with a heart of gold, and is more of a light-hearted parody of the genre. 1988's Deathstalker and the Warriors from Hell and 1991's Deathstalker IV: Match of Titans return to a more straight-faced sword & sorcery style, but are still considerably lighter than the first film. Deathstalker was portrayed by Rick Hill in the first and fourth films, John Terlesky in the second, and John Allen Nelson in the third.

- Ewoks: The Battle for Endor (1985): Yes, even Star Wars got in on the act! The second of two Ewok television movies, Battle for Endor is a science fantasy take on the genre aimed at a younger audience. The villain of the piece, Terak, is a towering alien warlord whose soldiers wield axes and scimitars alongside their blasters, ride horses and blurrg-drawn wagons, and are assisted by a shapeshifting witch. In fact, most of the film's conflict is predicated on Terak not realizing what genre he's in, as he believes that random spaceship engine parts he's collected are magical artifacts that will let him escape the Forest Moon of Endor. Would probably make a solid introduction to the genre for younger audiences.

- Amazons (1986): A loose, expanded adaptation by Charles R. Saunders of his short story "Agbewe's Sword", the first of his Dossouye stories. Mostly notable for being the only adaptation to date of Saunders' work, though it was whitewashed into a generic fantasy setting rather than the Dahomey-inspired setting of the original story, with the Dossouye-equivalent renamed "Dyala". Still a fairly entertaining film in its own right, but definitely a waste of potential.

- The Barbarians (1987): Starring real-life identical twin bodybuilders Peter and David Paul, also known as the Barbarian Brothers, The Barbarians explores the immortal question, "What if Schwarzenegger's Conan got split into two guys, but had to share the one brain between them?" The result is a gloriously silly romp as two colossal meatheads try to rescue their adoptive mother from an evil king. Notable for being written by James Silke, who would go on the write the Death Dealer novels.

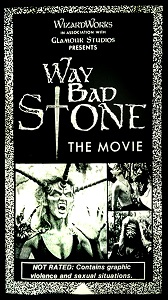

- Way Bad Stone: The Movie (1991): An ultra-low-budget, shot-on-video dark fantasy from Florida, Way Bad Stone is unusually gory and nihilistic even by sword & sorcery standards. After a band of adventurers steal a wizard's magical stone, he hires another band of adventurers to steal it back, leading to grisly ends for all and sundry.

- The Scorpion King (2002): Probably the most high-profile sword & sorcery film post-2000. The Scorpion King is a spin-off of 2001's The Mummy Returns, detailing the origins of that film's monstrous Scorpion King as Mathayus, a heroic Akkadian assassin. Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson plays the title role, reprising it from The Mummy Returns, in his first starring role. Was followed by four sequels, with rumblings of a reboot in the works.

- Wolfhound (2006): Based on a 1995 Russian novel by Maria Semenova, Wolfhound borrows heavily from Conan the Barbarian; Wolfhound's village is slaughtered and he is enslaved while still a child, just like Conan. It soon goes off in own direction, though, and it's a very enjoyable film with some likable characters and great visuals.

- Conan the Barbarian (2011): Attempts to hew closer to Howard's vision of the character, and largely succeeds in that regard, but fails in most others. Conan 2011 has some great action and a more believably savage, uncivilized hero courtesy of Jason Momoa, but bland writing and a generic plot let down the potential.

- Mandy (2018): Nicolas Cage stars as a lumberjack out for revenge after a drug-addled cult leader destroys the life he's built in California's Shadow Mountains. Though it's set in 1983, Mandy borrows heavily and openly from the themes, imagery, and archetypes of sword & sorcery, with Cage's axe-swinging, increasingly unhinged Red as the barbarian hero and Linus Roache's lustful, hedonistic Jeremiah Sand as the sinister, lascivious priest or sorcerer. A quote from Esquire on the DVD cover calls it a "psychosexual hallucinatory heavy-metal grindhouse revenge saga", which is as good a way to put it as any.

- The Northman (2022): Robert Eggers' viking revenge epic is, I think, a borderline case, but is likely to be of interest to readers. Based on the legend of Amleth, the inspiration for Shakespeare's Hamlet, The Norseman is a stark showcase of the inescapable cruelty and brutality of the Old Norse ethos and the viking lifestyle, a deliberate repudiation of the romanticization of the northern barbarian. We see vikings betray their kinsmen, massacre and enslave civilians, mutilate the dead, and ultimately realize the inescapable cycle of violence they've created for themselves. Pretty cool stuff!

Sword & Sorcery Links

Inspired to do some reading? Here are some online sword & sorcery resources!

- Works by Robert E. Howard at Project Gutenberg and Faded Page

- Works by Clark Ashton Smith at Eldritch Dark

- "The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth" (1908) by Lord Dunsany, often cited as a sword & sorcery tale that predates Howard's setting the formula.

- Black Gate, an excellent online magazine covering all sorts of fantasy, sci-fi, horror, pulp, and weird fiction.

- Dark Worlds Quarterly, an online magazine dedicated to pulp fantasy, sci-fi, and horror.

- "On Thud and Blunder" by Poul Anderson, a critical essay about the importance of research, logic, and realism in writing fantasy fiction.

- Pulp and paperback fantasy cover art at Pulp Covers

- Weird Tales magazine archive at Internet Archive

- Charles R. Saunder's old website, which includes his blog and various articles. His newer website also has some interestng material on it.

- Heroes of Dark Fantasy, an old fansite by author Dale Rippke with sub-sites for Brak the Barbarian, Conan the Cimmerian, Druss the Axe, Elric of Meniboné, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, Imaro, Kane, and Kull of Valusia.

- The Unofficial Frank Frazetta Fantasy Art Gallery

- Grim Dark (Half Off), a Youtube channel dedicated (in part, anyway) to dark fantasy and sword & sorcery, including lore videos covering Howard's Hyborian Age and similar fantasy settings.

- A memorial page to sword & sorcery author Lin Carter

- The Barbarian Keep, an old fansite dedicated to Robert E. Howard and historical "barbarians".

- The Savage Website of Conan, an old Conan fansite with great information on the Hyborian Age.

- An old Conan the Barbarian fansite.

- The Many Faces of Hercules and Other Hercules Heroes, profiles of actors who've played Hercules and other peplum heroes on the silver screen.

- "The Kings of the Night: A A History of Sword & Sorcery" by author G.W. Thomas.

Return to homepage